- Home

- LaGreca, Gen

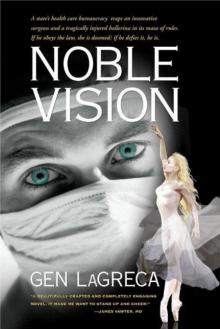

Noble Vision

Noble Vision Read online

Noble Vision

Gen LaGreca

Winged Victory Press, Chicago

www.wingedvictorypress.com

Copyright © 2004 by Genevieve LaGreca. All rights reserved.

Published by Winged Victory Press, P.O. Box 16730, Chicago, IL 60616-0730; www.wingedvictorypress.com.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and events are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or deceased, is purely coincidental.

Cover design by Holly Smith and Elizabeth Watson

First printing 2005

ISBN for bound editions:

hardcover 978-0-9744579-8-7; quality paperback 978-0-9744579-4-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2003113981

Quality discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For information, please contact:

Winged Victory Press, P.O. Box 16730, Chicago, IL 60616-0730;

www.wingedvictorypress.com

Email: [email protected]

Praise for the print editions of NOBLE VISION

A ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year Finalist

and Writer’s Digest International Book Awards Winner

A beautifully crafted and completely engaging novel. I read it in one sitting. It made me want to stand up and cheer! ---JAMES VAWTER, MD

A gripping story superimposed on today's threats to quality medical care. . . . Admittedly a novel, it is filled with truths of today. ---EDWARD ANNIS, MD, Past President, American Medical Association

Noble Vision is a wonderful literary achievement. An extraordinary hero, a tender love story, a fascinating medical discovery, and an intense family conflict are dramatically interwoven in a plot that surprises and delights. ---EDITH PACKER, JD, PhD, psychologist

. . . Noble Vision captivated me from beginning to end. Its grim vision of the near future---or is it the present?---of medicine is all too accurate. Can a few men and women of principle turn it around? One must have hope. ---JANE ORIENT, MD, Executive Director, Association of American Physicians and Surgeons

The defects of government-controlled medicine are dramatized effectively in this page-turning story of the love of a brilliant physician for a beautiful ballerina who becomes his patient. ---MILTON FRIEDMAN, Nobel laureate economist

Salutary tale of what can happen to medical breakthroughs if Big Government claws even deeper into our healthcare system! ---STEVE FORBES, President and CEO, Forbes magazine

Noble Vision is a suspenseful tale of one surgeon’s heroic struggle to save his work and the woman he loves. It inspires us to search inside ourselves for what we know to be true---and to seek the courage to live by it. ---BETH HAYNES, MD

. . . an intriguing novel about how unintended consequences of good intentions can have a devastating impact on the healing professions. ---WALTER E. WILLIAMS, syndicated columnist

Noble Vision is a chilling suspense story, with an intricate plot that thickens as the author explores deeper and deeper into the lives and minds of the characters. A well-researched . . . sensitively written . . . inherently captivating novel of suspense, Noble Vision is very highly recommended reading. ---MIDWEST BOOK REVIEW

The novel deals with some of the most serious issues of the day, lending the story an immediacy and vibrancy. The author's prose is polished and professional. ---WRITER'S DIGEST magazine

A fiction reader’s delight! Noble Vision has villains you will despise and heroes you’d love to meet. Add intrigue, betrayal, romance---you’ll be captured till the end and long for Gen LaGreca’s next novel! ---KAREN TIERNEY, MD

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Dr. Gail Rosseau, a Chicago neurosurgeon, for generously answering my questions and explaining neurosurgical techniques to me at the start of my research. I also deeply appreciate the medical editing that the book received from Chicago-based Dr. Robin Wellington, a neuroscientist, and Drs. Kirk Jobe and Juan Jimenez, neurosurgeons. These professionals gave me vital technical information and suggestions. We did not, however, discuss the theme or message of the story, which represents my view and not necessarily theirs.

The manuscript profited from two readings by Dr. Beth Haynes, a physician in northern California, and from the diligence of my excellent copyeditor, Katharine O’Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit. Dr. A.J. Mundt, a radiologist, patiently answered my numerous medical questions. Other doctors, nurses, and hospital staff members kindly assisted me in my research.

A very special thank-you goes to Dr. Michael Schlitt, a neurosurgeon in Seattle, Washington. His technical advice and creative ideas helped me enormously in molding the medical aspects of the plot. Any inaccuracies in the fictional adaptation of his suggestions are my doing.

I am profoundly indebted to Dr. Edith Packer, a clinical psychologist in Southern California. She edited the manuscript, offering invaluable psychological insights into the characterization. And it was she—more than anyone else—who encouraged me to write fiction. When I did, it quickly became my life’s passion.

Contents

Part One: Fire

1. The Dancer and the Phantom

2. The Banquet . . .

3. . . . And the OR

4. The New Frontier

5. Hide and Seek

6. Unnecessary Treatment

7. The Last Chance

8. Payment Due

9. The Threat and the Promise

10. On Shaky Ground

11. The Diagnosis

12. The Treatment

13. The Morning After

14. The Outlaw

15. The Law

Part Two: Thunder

16. The Model Citizen

17. A Light Extinguished

18. The Phantom Returns

19. Abraham and Isaac

20. The Doctor and the Dancer

21. On Trial

22. Trapped

23. The Final Verdict

Part Three: Hope

24. A Colorless Day

25. Close Friends

26. The Unexpected

27. The Raise

28. Approval Pending

29. Meeting Overdue

30. No Deal

31. Everything’s Going to Be Okay

32. The Phantom’s Plea

33. Necessary Treatment

34. The Wake-Up Call

Epilogue: Should a Man Receive Flowers from a Woman?

Part One: Fire

Chapter 1

The Dancer and the Phantom

The bus terminal was a study in gray, with its vertical steel beams, smudged windows, scuffed slate floor. Dusty cones of light descended from metal canisters along the charcoal ceiling. A concrete overhang outside the building kept the sunlight at bay. Lines of people waiting to be processed snaked around silver stanchions near the counters and boarding gates of the hollow station. One person in the crowd, a teenager with a child’s long legs and woman’s budding breasts, was tired of waiting, her restlessness apparent in the constant shifting of her weight and the tapping of her fingers in her folded arms.

As she approached the ticket counter, she saw gray-uniformed clerks boxed inside a row of booths resembling prison cells. The buses outside, pushing back from the gunmetal frame of the building like dead bolts sliding open, filled her with the daring hope of escape, for the destination of one of them was her future.

“Anyone traveling with you?” asked the ticket agent from behind his glass partition.

“No,” said the girl.

“I need to see your ID.”

She slid the driver’s license of an eighteen-year-old under the partition, although she had just turned thirteen.

The agent’s eyes darted

suspiciously from the license to her face, making her knees tremble and her hands sweat. Fighting a quiet battle against a familiar enemy, panic, she forced her eyes to hold on the agent’s unsmiling face. She had applied heavy makeup, worn glasses, pulled childlike blond curls into a frumpy bun, and practiced a deep voice so she could buy a one-way ticket across the country—and with it, a new life.

“What’s your name?” The agent’s words ground coarsely through the microphone.

“Nicole Hudson.” The name and the license were one day old.

“Address?”

“Three-forty-three West 18th.”

He waited.

“Here in Manhattan,” she added.

“And what’s your Social Security number?”

She recited the number she had memorized from the phony license.

“Which Motor Vehicles office did you go to for this license?”

Fear pulled her eyes down. Was there something on the license that identified the issuing office, or was the agent bluffing? The man selling her the phony document had not mentioned this matter. She had paid him eight hundred dollars with money stolen from her foster family, money she would repay, for she had never taken anything before.

Her fingers tightened around a small bag curled in her arm. The parcel contained the remnants of her first ballet shoes. She had preserved the tattered slippers like an heirloom in a fine leather purse, although the rest of her belongings hung from her shoulder in a cheap vinyl bag. During the split-second pause in the most important conversation of her life, she clung to the outgrown slippers the way a younger child might grasp a teddy bear.

“I asked you where got this driver’s license,” the clerk squawked.

She knew of a Motor Vehicles office in the same building as the courtroom that heard cases brought by the New York State Department of Child Welfare.

“I got it at the municipal building on West 28th Street.”

The tired entity that was the clerk returned the license. He didn’t seem to notice the relief filling the blue eyes almost to tears and the tension draining from the slim shoulders. He didn’t seem to notice that beneath layers of eye shadow were the wide eyes of a child.

“Where to?”

“San Francisco.”

“Round trip?”

“One way.”

When she’d felt driven to leave New York’s stifling depot of foster care, San Francisco had become her destination. She knew of a great school for ballet there called the Benoir Academy.

Gracefully, she lowered her head to gather her cash, wondering if anyone had reported her missing or was looking for her. Apparently no one had or was. She paid the clerk and took her ticket.

Walking to her gate, she didn’t hear the sterile music piped through the loudspeaker. Instead, she hummed a joyous melody from the first ballet she had ever seen, at age six, sitting with a group of vagabond children. Their unsupervised playground was Manhattan, except when they were gathered, washed, and fed by the nuns of St. Jude’s, a parish in her neighborhood. Their ballet tickets were a gift from an anonymous church benefactor. Perhaps because many of the youngsters had entered the world trembling from one addiction or another or routinely visited relatives in jail or witnessed more violence in real time than on any movie screen, the supreme innocence of the ballet provoked in them only jeers.

But the little girl with the long blond hair never noticed their snickering as she sat hypnotized by the magic of the stage. She saw an enchanted forest of tall trees cut by a watercolor meadow of pastel pink and powder blue flowers. A lovely princess danced with a young prince in an unimaginable world of beauty and goodness.

After that day, the chaotic events of her life became simple. The ballet reduced all choices of true or false, right or wrong, life or death to one golden rule: To dance was good; not to dance was bad.

Her first ballet slippers were the child’s bounty after weeks of rummaging through the trash outside Madame Maximova’s School of Ballet, where the affluent children of a nearby neighborhood took classes. Worn and discarded by a young student, the slippers got a second chance at life—and gave one to the future Nicole Hudson. They became the one absolute in her otherwise uncertain world.

The slippers were with her the day her mother—never quite stable or sober—told her, “Get your things together,” then left her on the steps of St. Jude’s Parish. “Tell the sisters I’ll be back for you soon,” said the drawn figure whose unkempt hair and dark-ringed eyes added a troubled decade to her twenty-five years. The child of eight carrying a shopping bag of clothing stared at her mother blankly. “And don’t be a pest and ask a lot of questions, Cathleen. Do what they say, you hear?”

Her mother never did come back, so the ballet slippers assumed the role of surrogate. They were the child’s solid footing through a revolving door of foster families. When she was frightened, their soles whispered of a better life. When she cried, their cloth wiped her tears. The slippers were with her in the courtroom at age ten when she was pronounced abandoned and eligible for adoption. And the shoes were with her when she peeked at a paper in her file on a caseworker’s desk that declared she was “maladjusted” and “unadoptable.”

The slippers fit her feet in the early years when she danced on her first makeshift stage, the cramped living room of the tenement where she lived with her mother. To clear a space for her future, the child would push aside the clutter from her mother’s disheveled life—the tattered armchair hauled there from a pawnshop, the chipped-veneer coffee table, the pages from a two-day-old tabloid strewn around the room, the soiled plates from the previous night’s supper eaten before the television set, and an array of empty beer cans. Under a rust-colored water ring that stained the white ceiling like an old wound, the little princess would dance. Her mother, who had not yet decided what to do with her own life, could not understand how the child just knew what she herself would do with hers.

The girl became a persistent, uninvited presence at Madame Maximova’s, searching for chores to do—sweeping floors, removing trash, cleaning locker rooms. The teachers objected at first to her unsolicited labors, chasing her home. But like a pesky squirrel hunting for food in its indomitable struggle for survival, the child kept returning. Eventually, the staff grew accustomed to her after-school assistance. Thus, she was allowed to take classes for free. Through the years, she continued to do chores—running the reception desk, enrolling students, issuing bills—without ever asking for money or receiving any. She just took the classes she wished for free, and no one stopped her.

When she learned her first steps, the slippers were on her feet. They arabesqued and pirouetted—and fell—with her. They and their successors covered frequently tired, sometimes blistered, but always nimble feet. They sat idle for periods in which she was sent to the dreaded suburbs, to foster families that comprehended nothing of the divine world of Madame Maximova’s, which she missed desperately. Hence, she would run away to the shelter at St. Jude’s and to her beloved classes. She returned to the sweet torture of exercises repeated hundreds of times until swollen, bleeding feet no longer could hold her. She took her lumps proudly, for pain was not a valid reason to stop. Then she would be retrieved by social workers who thought they knew best.

But that was in the past, when others were in charge. Now there would be no interruption of her training, she resolved, clutching her bus ticket, hoping it was not too late.

A toneless voice over the loudspeaker announced the most thrilling news of her life: “Gate sixteen to San Francisco now boarding.”

Suppressing the wild cry of laughter swelling in her throat, she climbed the narrow steps into the musty vehicle, then found a seat. As the skyscrapers of Manhattan faded to a jagged gray backdrop in the rear window of the bus, she counted her money. Fifty dollars left. She smiled, unworried. She laid her head back and closed her eyes on the serene vision of fairies dancing in an enchanted forest where she was the princess. That day, an indifferent world barely no

ticed the last of Cathleen Hughes, homeless child of thirteen, and the first of Nicole Hudson, woman of eighteen.

* * * * *

On a July afternoon ten years later, the Taylor Theater of Broadway carried a hushed audience back to the dawn of mankind. A packed house formed a crescent of rows around the legendary stage. The chandeliers’ starlike clusters of light slowly faded to black on the gilded ceiling of the historic building. With the luxurious rustle of soft velvet, the massive red curtain rose on a ballet that had become a Broadway sensation: Triumph.

The stage was divided into two opposite realms. On the left stood a white Doric temple rising from a grassy knoll into a slate blue night sky. Torchlights flanking the entrance cast a brilliant golden light over the scene. Ballerinas in sheer pastel gowns danced gaily to a pastorale. Male dancers joined them, clad in princely white tunics with full, flowing sleeves fastened tight at the wrist. The playbill described the realm as “an untroubled world of warmth, light, and beauty—Olympus, the home of the mythological Greek gods.”

On the right, a dusty yellow stretch of barren field with shiny patches of frost faded into a charcoal sky. A straw hut stood swaying like an injured soldier. Icicles hung in slippery spikes from the roof. Missing from this world were the lively torches of Olympus, and with them the life-giving warmth, light, and gaiety of that world. Also absent were female figures to soften the stark landscape. Men in brown tunics shivered in the cold, dancing dispiritedly to a somber theme. They laid an animal carcass on a wooden altar, then, turning to the deities of Olympus, groveled on their knees, bowing their heads and offering their sacrifice. The playbill described this scene as “the first mortals on Earth in the Greek legend of man’s creation.”

Noble Vision

Noble Vision